Before very recently, I knew very little about Dallas, Texas.

That changed for two reasons. First, it’s the location of the site used for this year’s Urban Land Institute Hines Student Urban Design Competition. I was a member of a team at the University of Maryland that submitted an entry, creating a land use and development plan for a long-neglected district near downtown. Regrettably we did not win, but it was great fun and involved a crash course in Dallas architecture, planning, and history. Second, I was invited to my friend Eric’s wedding, which is to be held next weekend in Dallas, his fiancé’s home town. The trip will provide the opportunity to visit downtown, and if time allows perhaps even the project site.

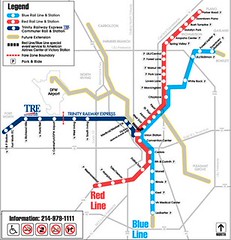

One of the surprising findings from my ULI research was the city’s extensive light rail system. My previous post on Light Rail in unlikely cities neglected to mention Dallas. After a transportation planning process in the 1990s, Dallas Area Rapid Transit began building a light rail system. The first portion opened in 1996, and today the system carries an average of 63,400 passengers daily over 45 miles of tracks seen in the system map to the right.

One of the surprising findings from my ULI research was the city’s extensive light rail system. My previous post on Light Rail in unlikely cities neglected to mention Dallas. After a transportation planning process in the 1990s, Dallas Area Rapid Transit began building a light rail system. The first portion opened in 1996, and today the system carries an average of 63,400 passengers daily over 45 miles of tracks seen in the system map to the right.

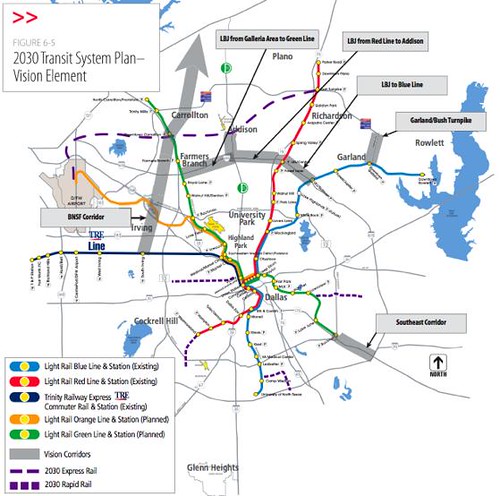

However, planned extensions in various stages of planning and construction will over double the size of the system, bringing the total to over 91 miles. (As a point of comparison the D.C. Metro is 106.3 miles) Here’s what the system will look like when planned work is complete.

The full plan officials are working from has even identified additional corridors for transit.

What is the larger economic and social context of this development? A 2004 study by the Dallas Morning News described Dallas at the “tipping point,” identifying underperforming schools, a weak tax base, low quality of life, and a slow economy in the center city. What’s missing from the detailed report is how little the spatial forces are explicitly recognized in the report. Sprawl is made possible by transportation infrastructure and land use policies, and any comprehensive solution must come from these sectors. The symptoms of sprawl are clearly described in a 2005 “update” to the original report:

Unchallenged, the report said, the city will continue on a downward spiral.

It works like this: High crime and cratering schools send droves of middle-class families into communities like Frisco, Rowlett and Garland. Eventually, businesses follow. Dallas sales and property taxes plummet, reducing funds the city needs to fight crime and fix its schools.

Evidence of the outward migration can be seen on a drive north, 25 miles out of the city, through a sea of tri-level trophy homes in communities with double-digit growth.

The light rail transportation infrastructure being developed is necessary but not sufficient to counter these problems — also necessary is the political will to coordinate land use policies, control fringe development, and tackle stubborn problems like crime and education. The agency’s aggressive pursuit of transit oriented developments (a building is already under construction adjacent the future light rail station in the photo at the top) is a positive sign, but with only 63,400 riders a day the system has a long way to go.

Pingback: Transistasis: A Plan for Dallas’ Cedars Neighborhood - The Goodspeed Update